A Trail of Murder and Revenge in Papua New Guinea

Last September, a trekking company's guided trip through the wilds of Papua New Guinea was shattered when machete-wielding men attacked the native porters, killing two on the spot and injuring many more. The motive appeared to be robbery, but Carl Hoffman knew something else was at work—ancient tribal patterns of violence that, he knew, would inevitably be avenged

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

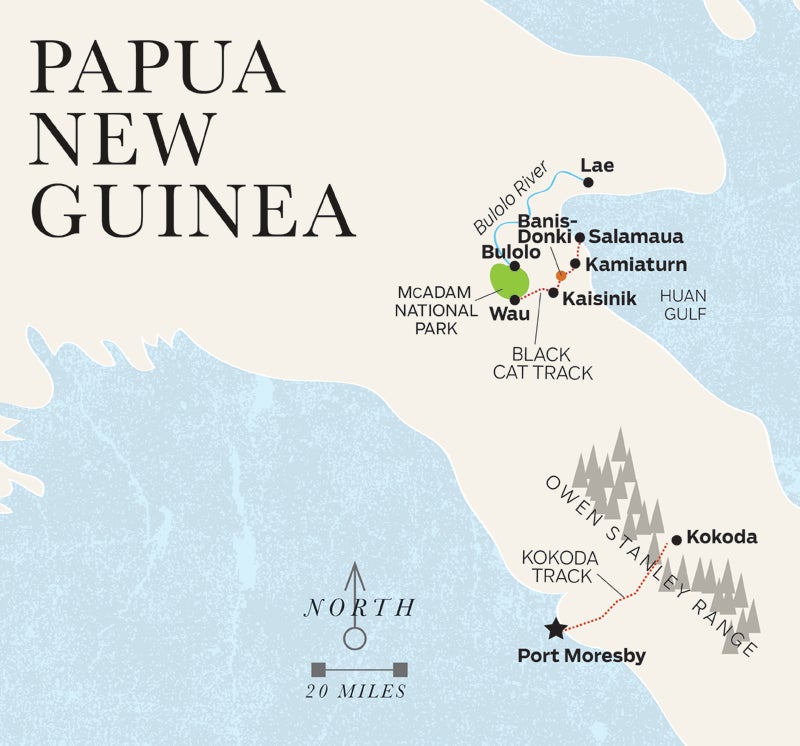

States of grace can be elusive, but Christy King had found hers, if only for a moment. It was 3 P.M. on Monday, September 9, 2013, and King was basking in the glow of a well-ordered campsite. The 39-year-old Australian had just finished her first day leading seven Australian men, one New Zealander, and 19 local porters on a planned six-day trek in Papua New Guinea, from the highlands down to the coast, along the Black Cat Track, an arduous, precipitous, and overgrown 42-mile trail first opened by Aussie gold miners in the 1920s and later the site of one of Australia’s most harrowing battles in World War II.

They’d started walking at six that morning, through an epic landscape that began as steep hills covered in high grasses. The clients ranged in age from their early forties to 67, but King was surprised by their high level of fitness. By 2 P.M. they’d made the first campsite, at Banis-Donki, a clearing set amid thick jungle with the trail entering and exiting at either end. In a cold drizzle, the porters went to work, setting up an orange tent for each trekker. For themselves they strung a silver-colored tarp from the trees.

They slashed and cut and cut and slashed—the legs of almost every porter, slicing their calves and Achilles tendons, chopping so fiercely that bones shattered.

The clients quickly disappeared into their tents to change into warm, dry clothes. The porters started a fire and put water on to boil. Porter Kerry Rarovu, hungover, just wanted to crash. King had known him for years, and as she horsed around with him and other porters under the tarps, she stood where he was trying to set up his bed. “Get off!” he barked, jokingly. “I need to sleep!” Matthew Gibob, another porter, flopped down next to Rarovu.

The rain stopped, and Rod Clarke and a few other clients emerged. It was often rainy up here in the high hills, and nobody minded—that was part of the adventure. Smoke from the cooking fires swirled around the campsite as rice bubbled in pans of water. Nick Bennett was still in his tent. Zoltan Maklary was in his, listening to his iPod. A few of the boys, as the porters called themselves, were collecting firewood in the forest.

Everything was perfect. And then the men with machetes burst out from the trees.

They entered the clearing from the far end of the track, fast, with a level of aggression that shocked King. Three men, each wearing homemade balaclavas with small eyeholes, sprouting strange little ears, like Halloween masks. One carried a World War II–era .303 rifle, the two others three-foot-long machetes, known as bush knives in PNG. One of the machete carriers also had a sawed-off shotgun. The men were short, small.

“Sleep! Sleep! Sleep!” they yelled, pidgin English for “lie down.”

Clarke and the others hit the ground. King went to her knees.

Rarovu woke up just as the men swept in and started slashing the tarp and its guy lines. He opened his eyes, lifted his arm. The first blow came down, cleaving his hand in two along its length, between the middle fingers. The next blow split his skull open. And the next and the next. Eight times. The thumping sound was unforgettable.

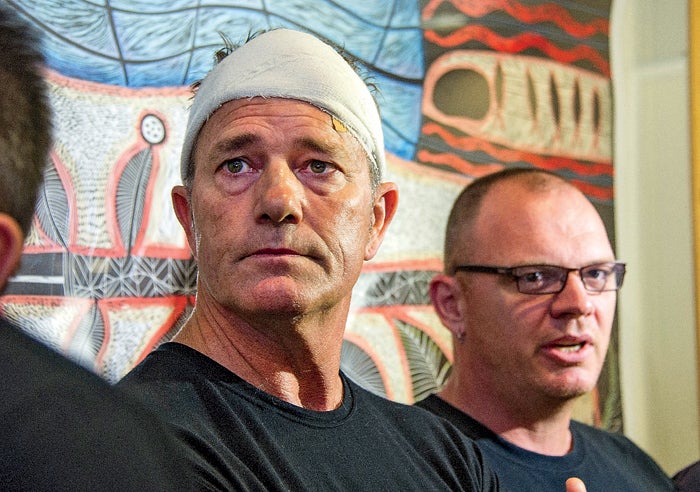

Bennett, in his tent, heard shouting. He thought something fun might be happening outside; maybe the boys had found a cuscus, a species of possum. He grabbed his camera and was about to exit the tent when he felt a crushing blow, heard an explosive noise in his brain. He thought he’d been shot, but he’d been hit by a rifle barrel. Blood poured from the wound.

Maklary shifted in his tent and started to take out his earphones when a blade came crashing down into his arm.

“Want the boss man!” the attackers screamed, striking the Australians with the flat sides of their machetes.

The men cowered on the ground.

King stood. “I am. What do you want?”

“Money, money, money, money,” they shouted.

King’s tent was at the end of the row and she got up, pointed to it, said the money’s in there—she was carrying half the porters’ wages and all the money they’d need for paying villagers along the route, about $5,000. The attackers separated her from the others, made her get the money out of her tent. She thought they would just grab the cash and run. But as the man with the .303 stood watching while she gathered it, the other two ran back and forth in a frenzied state, rifling through the tents, slashing any porter who moved.

“Sleep! Sleep! No look!”

They hacked Gibob, lying next to Rarovu. They shoved Peter Stevens’s pointed walking stick into his calf. They yelled for Bennett’s camera and the money in his pockets, and then they brought a machete down, hard, into a tree next to him to emphasize the command. They slashed and cut and cut and slashed—the legs of almost every porter, slicing their calves and Achilles tendons, chopping so fiercely that bones shattered. The trekkers were lying down, listening to the thumps, the screams, but King was seeing much of it, thinking, planning. What was she going to do?

Silence.

“Have they gone?” someone finally said.

The survivors raised their heads. Stood. Twenty, maybe 30 minutes had passed. The camp was destroyed, tents, sleeping bags, backpacks, clothes strewn everywhere. Bennett watched Matthew Gibob take his last breath and die. Dick Reuben, another porter, was in shock, his eyes rolled back, as Bennett dressed him, put socks on his bloody feet. A few of the porters, who’d been out collecting firewood when the attackers came, were gone, disappeared into the bush. Porter Joe Gawe had ducked his head just enough as a machete nicked his face, then raised his arm as the next blow came, slicing his forearm. All the others were cut in the legs, unable to stand—except for two: a nine-year-old son of a porter, and a porter who held the boy when the attack was under way.

“It was horrific,” King told me two months later. “Like a war zone. I’m a nurse and used to seeing flesh and death and the shitty things that can happen to human beings. But Rarovu was butchered. His head was massively split open, and there were limbs and bodies and blood everywhere.”

“Christy, Christy, help us,” the porters cried. “We’re dying.”

King went into autopilot. She located the first-aid kits, threw around bandages, and found one of the trekkers’ Australian cell phones. It had a signal—they were still in range. She couldn’t get a local number but reached her father-in-law in Australia, told him they’d been attacked, told him to call her husband, who lived in PNG. She found a PNG phone, called a friend who worked for Morobe Joint Mining Ventures, the operator of a giant gold mine near the start of the trek, called everyone who could help, said to send villagers up the trail.

She ran the numbers. Thought about her responsibility to the clients, who were bleeding, traumatized. Dark was coming, and in the highlands that meant a long, cold night. She decided. They’d bandage everyone up as best as they could, make the porters as comfortable as possible, and walk out the way they’d come, a roughly six-hour trip. “It was hard to leave them, but we couldn’t do anything more, and we needed to get help,” she said.

The only problem: that was the direction the attackers had gone, too. “It was eerie and scary,” King said. “We’d walk for ten or fifteen minutes and smell their marijuana, stop, keep to a tight group.” They had headlamps but were too afraid to turn them on, so King led them stumbling through the darkness.

“Adrenaline kept us going,” said Bennett.

After several hours, they encountered a mass of villagers on the trail, and by 10:30 P.M. they were in the Morobe Mine’s clinic.

But the porters were still up there, on the killing ground.

The attack got little attention in the United States, but Papua New Guinea—an independent nation covering roughly 173,000 square miles on the eastern half of the island of New Guinea—is a former Australian colony that gained independence in 1975, and within 48 hours the trekkers were home, their ordeal exploding across TV, radio, newspapers, and the Internet. Accounts invariably showed photos of Bennett with his head wrapped in gauze, reported that Stevens had been speared, and called the attackers robbers or bandits. The more thorough stories included a line or two quoting locals who said a dispute between tribes may have played a part—a theory that Mark Hitchcock, one of the owners of PNG Trekking, the company that sponsored the trip, disputed. The motive, he told reporters, was clearly robbery. “This is an isolated … incident that shocked us all,” Hitchcock was widely quoted as saying. It was, he said, “totally out of character for the track.”

As the days passed, police on the ground and in helicopters combed the hills and jungles for the perpetrators. Then, a week later, came another story: relatives of a porter who’d died had attacked someone who was suspected of harboring one of the killers.

At first I watched this all unfold from afar in the U.S. Having spent the past three years working on a book about the 1961 disappearance of Michael Rockefeller in New Guinea, I’d traveled for several months in remote areas of the island’s western half, Indonesian Papua, where I’d lived with a tribe on the southwest coast. Although tribal customs vary widely across the island, the idea of reciprocal violence—of balancing the world through constant warfare and the taking of what Westerners would call revenge and tribal people call payback—is nearly universal. Reports of horrific violence in PNG were becoming increasingly common, including attacks against people perceived as sorcerers—itself a form of reciprocation, this time against the spirits—who were causing trouble in corporeal form.

It wasn’t just happening in remote areas but in the country’s largest cities, too, like Port Moresby, Lae, and Mount Hagen, as men from warrior cultures became unmoored from the sacred customs governing and controlling that violence, then found themselves poor and jobless in cities and further removed from village and tribal embrace. Although the media spotlight shined on the Australian trekkers and their ordeal, one thing was clear: while Bennett had been hit in the head, Maklary slashed in the arm, and Stevens impaled in the leg with his walking stick, none of the clients had been badly hurt. Emotionally traumatized, yes, robbed, yes, but nobody had lost so much as a finger or required more than a few stitches. This in a crime characterized by brutal chopping. If they’d been struck at all, it had been done with the flat side of the machetes’ blades. A certain care had been taken.

The porters, who ranged in age from twenties to forties, were another matter. Two had been killed right on the spot, a third was so cut up he died within days, and six others had been brutalized with a specificity suggesting that what happened was a lot more complicated than robbery.

I was shocked by the incident but also curious about it, as a window into Papua New Guinea and what can happen when well-heeled Western tourists venture into the remotest corners of the world—complex places with deep cultural practices, emotions, and antipathies that Westerners little understand or are completely oblivious to. I wanted to know more.

Christy King was briefly quoted in initial reports, but then the woman widely hailed as the incident’s hero went silent. My e-mails to some of the Australians weren’t answered, until Rod Clarke finally wrote to say the trekkers were unable to speak further, because they were negotiating an exclusive media deal in Australia, a country with a long history of checkbook journalism. Finally, one day, I managed to get Pam Christie, the co-owner of PNG Trekking, on the phone, but she, too, refused to comment. None of this helps tourism in Papua New Guinea, she said, and it was time to move on. When I asked her to put me in touch with some of the porters or King, she said, “Absolutely not.” If I wanted more, I should call the PNG Tourism and Promotion Authority, which had been “fully briefed.”

I hired a friend in Australia, who managed to track down King’s parents, who passed on her telephone number, and when my researcher told King what I wanted to do—come to PNG to try and understand what had really happened—she said I could contact her. This loosened the tongues of the trekkers themselves, especially later, when their media deal fell through.

Two weeks after that I was in PNG, slowly assembling the picture.

Twenty-four hours before the attack, Nick Bennett was bumping along in the bed of a Toyota pickup in the highlands of PNG. He and the seven other Australians had just flown from Port Moresby, the country’s steaming capital, into Bulolo, an airport consisting of two converted shipping containers, and now they were going up, up, up into higher terrain.

It was wild and rugged, beautiful, the kind of place that makes your chest swell, makes you laugh out loud, makes you feel lucky. The road was dirt, rutted, potholed, passing through dense green jungle one minute, cutting along the edge of steep hillsides another. Sometimes the truck forded fast-moving streams, and the sky was huge and full of clouds that were gray, green, and white and were pierced with rays of sunshine, a sun that felt warm in the fresh, cool air of the 4,000-foot mountains. Sometimes they passed Papuans trudging along the road. Small, black-skinned men in shorts and T-shirts, carrying machetes, women in flowered meri blouses—the colorful muumuus introduced by Protestant missionaries 100 years ago—with net bags full of sticks or sweet potatoes hanging behind head slings.

Bennett felt thrilled. He was 55, originally from New Zealand, had served in the New Zealand police’s diplomatic protection corps and then moved to Australia, where he’d worked as a tour guide and trainer and had competed in the epic Sydney to Hobart sailing race. He loved adventure, exotic cultures, deep experiences—and then he’d been felled by a heart attack. Bennett fought back. He started doing yoga, began a 20-week fitness program that included long hikes and hill climbs, and now he was here at last, strong, healthy, triumphing over age, rocking along in the middle of nowhere. In terms of landscape and cultural strangeness, it doesn’t get much more intense, beautiful, weird—different—than PNG, and his journey was only starting.

Hikes like the one he’d signed up for are big business. The Kokoda Track, a much more famous trail than the Black Cat, is traversed by some 4,000 tourists a year and is “the single most important experience for Australians visiting PNG,” according to a 2012 economic analysis of Australian tourism. The hike runs from Port Moresby to Kokoda through the Owen Stanley Range, and it’s a well-oiled machine. Trekkers pay companies like PNG Trekking Adventures, which then contracts out for guides, porters, supplies, and logistics. A locally run trail organization collects a fee from every trekker and manages the route. It’s all so smoothly run, the guides and porters and villages they pass through so enmeshed in a well-developed business relationship, that there’s little crime on the track itself.

Looking to expand, the PNG Tourism and Promotion Board and PNG Trekking had begun opening up the Black Cat in 2004. Kokoda was already near capacity, and the Black Cat offered even more history and relics and raw challenge. Though shorter, it was far more technical, overgrown, and it passed through remote territories belonging to tribes like the Bong, Iwal, and Biangai. Developing it as a commercial trek promised a huge opportunity for everyone. But by the time of Bennett’s arrival, only a few commercial groups had actually done the trip.

Late that afternoon, Bennett and the others pulled into the village of Wau and a last oasis of sorts—the home of Danielle and Tim Vincent, longtime PNG residents and former colonial Australians who owned Wau Adventures, which they’d created to handle logistics for the start of the trek. Outside the Vincents’ fenced compound was jungle, dirt roads, the smell of smoke and dampness and dust, and all those inscrutable Papuans. Inside their house it was burnished wood floors and plush white overstuffed furniture and glass cabinets. Over wine and a big dinner, the eight men, all middle-aged and most former military, got to know each other and the woman who was to guide them and would have responsibility for their comfort and safety.

Their trip leader was blond and tan, and the men were startled by her beauty and poise. “I thought maybe she’d have her husband with her,” said Clarke, “and that if she was leading the group, it really must be safe.”

Christy King isn't a woman who needs any help from a man. A hard-charging Australian expat, she’s an intensive-care nurse and an endurance athlete. She’s lean and muscled, with bulging calves the size of knotted softballs. She exudes competence.

Married into a former Australian colonial family that operates the largest chain of pharmacies in PNG, as well as an expanding set of grocery stores, she is a member of the white Australian expat elite that still plays a powerful role in PNG’s economy and politics. Lae, PNG’s second-largest city and its largest port, is positioned just an hour across the Huon Gulf by boat from Salamaua, the village at the base of the Black Cat. Lae has been home to members of the King family for 50 years, and Christy and her husband, Daniel, had been living there for the past decade, starting a family that now includes two school-age kids. Christy spoke Tok Pisin, the pidgin English language spoken all over PNG, and the family knew everyone, from government officials to the locals in Salamaua, where the Kings maintained a rustic beach house.

King doesn’t sit still. She runs daily, starting at 5 A.M., on Lae’s ruined streets, trailed by guards in a vehicle. In 2011, she ran the Black Cat’s 42 miles (a journey that takes most trekkers six days) in 31 hours. She did that to prepare for a race on Kokoda—60 miles—which she finished in 30 hours. She was supremely fit, knew the terrain, the people, the local language, all the political players.

The expat's message to me was clear: in a culture where payback was standard, the understanding was that anyone who turned themselves in would be safe.

Just a few miles from the Vincents’ house, as the trekkers and King were celebrating the adventure to come, so too were Rarovu, Reuben, and 17 other boys in a village called Kaisinik. For uneducated men from villages without power, plumbing, and often even roads that access them, in a country with few opportunities, carrying loads for trekking parties was a plum job, paying $50 a day plus tips and whatever goodies tourists left behind, from hiking shoes to digital cameras. Even more important, proximity to affluent, educated tourists was an education in itself, exposing villagers to a wider world and whatever opportunities they might be able to leverage from that. Every village profited when the trekkers passed through. “We pay for everything,” King says. “Every bucket of water. Piece of fruit. Firewood.”

In the hierarchy of native porters and guides, Rarovu was a star, an example of what a smart, motivated, and ambitious Papuan villager could do. He was reliable, showed up on time in a society where Western notions of time don’t exist. Trekking agencies wanted to use him, tourists wanted him on their treks, and he’d risen to the status of head guide, earning an extra $10 to $20 a day, picking up Western ways easily. “Kerry had very good English,” says King, “and great relationships with all the expats.”

He had hiked on Kokoda, and he led all the treks on the Black Cat. Traveling en route, he stayed in the same hotels as the Westerners, ate dinner with them, felt comfortable doing so. An expat in Lae had given him a mountain bike, and before long he was doing wheelies and tricks and racing it in local expat events. His stature in his home village rose, as did his affluence, slight though it was. He built a wooden plank house in his village, opened a store in its front rooms, was becoming a big man providing for his two children and extended family. “We saw Kerry as our leader,” says his cousin, Hubert Koromeng. King had used Rarovu for all her challenging runs.

But he’d also gotten a little cocky and apparently had started drinking too much. So for this, her first time as trek leader, King chose another man, Dick Reuben, as head guide. Reuben wasn’t as experienced as Rarovu, but he was quieter, more thoughtful, a handsome, well-spoken man whom King instinctively trusted and liked. Also, he was from Salamaua, the beach village where her family had their house.

Once Reuben got the job, his first task was to begin hiking inland, up toward the trailhead, and King had told him to make sure he collected porters along the way from the major villages, so that the wealth of the operation would be spread evenly along the route. No village—and, more important, no tribe—should be left out.

Reuben had selected a handful of boys from his own village and recruited more on the way, and they hiked barefoot under heavy loads, 40 miles through steep mountains in two days. By Monday evening there were 19, including Rarovu, at the village of Kaisinik, in the house of Ninga Yawa, the chairman of the Black Cat Track Association. As King and the Australians celebrated a few miles away in Wau, the porters celebrated in Yawa’s palm-mat house without electricity or plumbing, chewing betel nut, smoking and partying late into the night. In a few days they’d all have $300 in their pockets, and if this trek went well, more tourists would be coming, a stream of money and opportunity for a people who had nothing.

I spent three days with Yawa, who took me into the highlands, to the start of the track, and put me up in Kaisinik. Far away from PNG’s cities and expat community, this was a separate world, a place where tribal and cultural identities and differences were powerful and stark and on everyone’s minds.

In PNG, especially in the highlands, tribal violence is always close by, and Yawa was a Biangai. He was relatively well-off: he drove a four-wheel-drive Toyota pickup, and his family had been village leaders for generations. As we bumped into Kaisinik—a grassy median nestled between steep hills, the fast-moving Bulolo River running past—he said that his house had once been five bedrooms, was made of plank, and was raised on iron pylons. Not anymore. Now it and all the other houses in Kaisinik were simple palm-mat affairs, the kitchens an open fire under a palm roof. In 2009, the neighboring Watuts, with whom the Biangais have been engaged in a land dispute for decades, raided the village with spears and bows and burned it to the ground, killing five. In a rare move, Yawa had convinced his neighbors not to retaliate; instead, they were fighting the Watuts in court. But things were still so tense that five men slept on the porch of the little hut I was given to sleep in. “Your safety is our responsibility,” Yawa said.

The next morning he took me up to the trailhead, where the porters and the trekkers had met for the first time in a cool drizzle. Despite the rain and low clouds, the place was sublime, a mostly treeless world of green grass carpeting steep, undulating hills, the ridges in the distance covered in thick pines, a high rainforest they’d reach in a few hours. It appeared to be uninhabited country, not a village in sight, but up there, in there, lived people, whole communities unconnected to the outside world. It was the chance to see those people, interact with them—and their porters and guides who themselves were from those places—that had drawn Bennett and Clarke and the others as much as the challenges of the hike and its history.

Bennett had hiked Kokoda a few years before. “The boys would sing, and it was a joy just walking in the jungle and getting to know the culture,” he’d told me. This time his porter was a shy, quiet young man named Andrew. “It was his first trek,” Bennett said, “and had it continued, I would have gotten to know him very well.”

As the other porters met their clients—one head guide, one for each of the eight trekkers and King, plus nine more to carry the food and tarps and cooking equipment—King was surprised to notice that Rarovu smelled of alcohol. And although King had told Reuben to hire porters from villages spread evenly along the trail, 11 of the 19 were from Reuben’s own village. Which meant that, at the end of the trek, three or four thousand dollars would be flooding Salamaua, with much less going to the others. Only one porter was from Kamiatum, two from Mubo, one from Goudagasule, and two from Skin Diwai. Rarovu and Gibob were from Biawen, just up the road from Kaisinik.

But it was too late to change the makeup of the porters. And King trusted Reuben’s decisions: he knew tribal politics better than she. For his part, Reuben believed then—and believes now—that the distribution of his hiring was fair and appropriate.

Around 7 A.M. the trek began, 27 men and King, the porters in baseball caps and bare feet under heavy backpacks, the Australians wearing brimmed bush hats and carrying hiking poles. Each porter walked behind his client, Rarovu and King at the rear. The trail led from the road down a steep hill and then began climbing into the grassland, a narrow, slippery track. By nine they reached the carcass of a World War II B-17 that lay broken in two but was mostly intact after crashing into the hillside 70 years before. Everyone posed for photos, grinning, looking excited even in the drizzly weather, Reuben and Rarovu kneeling, proudly holding up their most important tool in the bush—a long machete.

They set out again, soon reaching the ridgetops and entering a thick, wet stand of woods. It was foggy, cloudy; the trees dripped. The Australians were going deeper, in every way, into the folds and complexities of a very complex place that few whites, even longtime PNG residents like the Kings, fully understood. To the Australians it was all just wilderness. That night they would camp at Banis-Donki, and from there they’d head to the thatch huts of remote villages.

But the Papuans, I was learning from Yawa and the men who sat around his fire at night, saw it all differently. Salamaua was in a region of Bong-speaking coastal people scattered in distinct small villages; Reuben’s was called Lagui. As the track rose inland, it entered territory that looked the same but wasn’t—the home of the Iwal people, centered in the villages of Mubo and Bitoi. And then, toward the head of the track, it entered Yawa and Rarovu’s territory, the lands of the Biangai.

The Bong, Iwal, and Biangai all knew where their respective territories began and ended, knew who owned what, knew who was from where just by looking at them. And they all spoke different languages. PNG had been like that for 40,000 years, a patchwork of hundreds of language groups and tribes whose relationship with their neighbors over the next ridge or across the next river often had been either nonexistent or violent, though on the Black Cat Track everyone had always gotten along.

On the Black Cat, additionally, there was a difference between the two ends of the route and the middle. Lagui, along the coast, was an hour by boat from Lae and had been in contact with the outside world for 150 years. Though undeveloped, it had cell service, tourists coming and going, a small but constant stream of income. The same was true of Wau and Kaisinik and Biawen at the highland end, which were reachable by road and set amid coffee plantations and a large and growing gold mine.

But villages in the middle were wilder, poorer, had no cell service, and were connected to the world only on arduous footpaths. The villages along the track itself, like Mubo, at least saw the occasional trekker. Villages like Bitoi, across the ridge from Mubo, saw no outsiders at all.

“These legs have done so many things,” said a porter named Jeremiah Jack. “They walk up and down, and so they chopped them so they won't walk again.”

The Iwal in the middle wanted a system in which porters would work only inside their own tribal boundaries, with trekkers changing porters along the way, thereby ensuring that each region and tribe got work. But the trekkers and trekking companies didn’t like that arrangement. Trekkers wanted to get to know one porter for the duration of the hike. The companies didn’t want to have to deal with the complex logistics of switching porters around. And since most of the track went through Iwal country, the Bong and Biangai at either end would see far less work and revenue.

King was aware of these issues, as was everyone who lived in the area. A year before, she and her husband and Reuben had hiked up to Mubo, carrying a load of donated medical supplies for its clinic. The place had given her a bad feeling. But she thought they’d be OK, and she’d specifically asked Reuben to pick boys from every village.

King and the Australians didn’t know it, but in the village of Kamiatum, Reuben had encountered a group of men who questioned him. “They asked me if I was going to take porters from each village, and I said that’s what I was doing,” Reuben would tell me later. “I asked the boys where they were from, and they said Bitoi.” When King and the trekkers arrived at Banis-Donki to set up camp, the attack had already been planned, set in motion by that encounter. It was the only campsite that was remote, not in a village, away from prying eyes. And the attackers were there, waiting, hidden in the bush.

One evening at Yawa’s house, a large group of Biangai elders began arriving to discuss their land suit against the Watuts. One by one they trickled in, until more than 20 were sitting around an open-air fire, drinking tea and coffee, chewing betel and smoking. The fire crackled and the sound of the Bulolo’s rushing water filled the night as they recounted a much more detailed version of what happened after the attack.

The Australian clients stumbled down the mountain and were quickly flown home. But even as they were being sewn up that night, Wele Koyu, a former Kaisinik village counselor and veteran porter, gathered four policemen and 24 local boys and began hiking up the track after midnight, along with the Morobe Mines logistics officer Daniel Hargreaves. Arriving at the attack site at 4:30 A.M., they tended to the injured porters and cleared a landing zone.

“It was cold, there was blood everywhere, and the porters were crying,” Koyu said. In two helicopter flights that morning, the injured were taken to Lae’s Angau hospital. They got there at the same time that a massive bus accident flooded the hospital with more dead and injured. There they languished, without blood, antibiotics, or painkillers.

In a country not known for its police efficiency, the Kings and their friends called PNG’s prime minister, Peter O’Neill. “From the minute it started, expats took control,” an expat who had closely watched the case had already told me. They pressured O’Neill, pressured the police, made sure helicopters were up and operating, oversaw the hospitalization and treatment of the porters, talked to the police after every arrest. Immediately, a helicopter and a mobile reaction force—a well-trained and heavily armed unit of the federal police created to combat tribal violence—began combing the area around the track. After the injured porters had spent four days in the public hospital, the expats moved all of them to the private Lae International Hospital, even as a third porter, Lionel Aigilo, died from his injuries. The expat liaison began paying off one of the suspects’ brothers, “To keep channels open,” he told me.

The expat’s message to me was clear: in a culture where payback was standard, where suspects under police custody often “died” before making it to court, the understanding was that anyone who turned themselves in would be safe.

Which, in light of what happened next, was a pretty good offer. In the minds of the Papuans, there was no question about what had occurred: Kerry Rarovu had been assassinated. The big man who got all the work had been struck first, targeted and hacked into oblivion. Matthew Gibob, also from the Wau area, had been next. Just as obvious was where the attackers came from. Everybody believed they were Iwal people from the villages of Bitoi, Mubo, and Wapali, long jealous of the work given to the people from either end of the track—even though, since they wore masks, their faces hadn’t been visible.

“The next day, the boys from Kaisinik went out searching for the culprits,” Koyu said, leaning in close, “in two groups, and we searched day and night.” In the Western world, people often live anonymously, away from family, unattached electrons floating free from all bonds. In places like PNG, everyone is bound to something, and there’s nowhere to hide. In the villages, everyone knows everything: who you are, who your parents and cousins and aunts and uncles are, where you’re from by your language or looks. And in Papuan cultures, reciprocal violence is everything, and always has been. On Saturday, four days after the attack, the brother of Gibob, the second porter to die, caught wind of a family suspected of harboring one of the attackers in Bitoi.

“Matthew’s brother and relations” killed three, Koyu said. “They went in and cut them and chopped them and killed them with the bush knife.” As Koyu told the story, the men around us all nodded in approval. The act created no moral or ethical dilemma for them. Here, such violence was more than expected. It was necessary, and it was how the world was balanced.

There was nowhere to go, nowhere to hide, and the boys from Biawen and Kaisinik and Lagui were scouring the ridgetops, the valleys, the villages, ready to burn and cut anyone who had anything to do with the attacks. Jail was safer than trying to escape. On Sunday, the day after Koyu and a gang arrived in Wapali with a police patrol, three men surrendered in exchange for being whisked away in a helicopter. “Otherwise the boys would have butchered them, chopped them to pieces,” Koyu said.

King and the eight clients all insisted they’d seen only three attackers. But as the next month unfolded, ten men were arrested, every one turning himself in to police, including some of the uninjured porters themselves, who were connected to the three main culprits by their cellphone records.

The attack, it turned out, was an inside job. Though the exact sequence of events may never be known, and none of the alleged attackers has faced a trial yet, the basic outline seems clear. Three brothers from around Bitoi, one of them nicknamed Rambo, were career criminals who’d done jail time for robbery and murder. They escaped and, up in the hills around Bitoi and Mubo, heard of the coming trek, knew of the envy and resentment of their fellow Iwal, and knew of the cash the party would be carrying. Robbery and payback coincided, mated.

In the morning, Yawa drove me back down to Lae and I flew to the coastal city of Madang, where I found the wounded head porter Dick Reuben sitting in a hospital bed. Crowds milled around the grounds outside, filled the halls. In PNG hospitals, patients are responsible for much of their own care, so he was being tended 24 hours a day by a man named Labi, from Reuben’s village, Lagui.

Two months had passed since the attack, but Reuben’s wounds remained hard to look at. His left leg had healed, a Frankenstein-like scar running across the cut Achilles tendon, but he still had little movement in his foot. His right leg was another matter: a gaping pink gash, three inches long and an inch wide, remained in the meat of his calf, where the machete had sliced deep. It was a strange scene. After a week of reporting, I knew something Reuben didn’t—even as he languished, the police suspected Labi, his caretaker, of complicity in the attack. (At press time, however, Labi had not been arrested or charged with anything.)

I spent a few hours with Reuben, watched as the doctor checked his wound. Raw and open as it remained, it was clean, healing, and at some point soon he’d be allowed to go home. To what, exactly, was unclear. He could walk slowly, haltingly, but he’d never again carry a 40-pound pack up or down mountain trails, and he had no idea how he’d support his four children, the youngest newly born. I bought him a couple of bags of groceries and some cellphone credit, and flew back to Lae, where I boarded a local boat packed with 16 Papuans and one bandicoot and traveled across the Huon Gulf to his village.

Lagui is beautiful, a narrow isthmus of white sand between sparkling blue water. Quiet, with no roads, no cars, no engines, only the sound of wind in the coconut palms and children’s voices. The houses are palm thatch, lit at night by kerosene lanterns and candles. It is a lovely place, bursting with pink and purple bougainvillea, the perfect ending to an arduous hike through the mountains, from clouds and chill to brightness and balmy heat. But for the foreseeable future, there won’t be any trekkers coming, no tents pitched on its beach.

“Not until our demands are met,” said Nick Aigilo, whose brother Lionel was killed in the attack. I was sitting with Aigilo on the bamboo floor of his house, an open fire smoldering on a bed of mud. With us was a porter named Jeremiah Jack, who’d been sliced in both legs. He was quiet and shy, thin, with a wisp of a mustache, his English poor. He thought he was “about 22.” Now he was a cripple who could barely walk. “These legs have done so many things,” he said. “They walk up and down, and so they chopped them so they won’t walk again. It wasn’t just robbery.”

The Black Cat Track is closed, and no one—not Koyu up in Kaisinik or anyone in Lagui—thinks it will open anytime soon. The region remains tense. “The Iwal must pay,” Aigilo said. “What we call bel kol: money and pigs, traditional things, and until then the boys don’t want to see any Iwal around. We’ll crucify them.” For all the people inland along the track, it remains the only route to the outside world—either through Kaisinik and Biawen in the highlands, or through Lagui to the coast and to Lae. Already, they say in Lagui, two people from interior villages have died because they couldn’t get to the medical clinic on the coast.

I walked through the quiet village with Gilan Sakiang, the local elder. Lionel’s grave looks over the sea, covered in masses of colorful plastic flowers. His mother accosted me, weeping. “Why?” she said in English. “Why have you come to remind me of Lionel?”

PNG Trekking paid for funeral services for the dead but won’t pay anything further to the maimed porters, maintaining that PNG’s worker’s compensation law should take care of them.

“We sit here and look at the white men’s houses,” said Sakiang, “but we get much more from tourists on the Black Cat. Now we have nothing.”

The trekkers themselves are shaken but moving on. They have created a fund to help pay for their porters’ medical expenses, but the idea—to hike the track again with a TV crew—fell apart. Things were just too unsettled, too hot.

Which is a common sentiment, often expressed by people who think of themselves as travelers, not just tourists, people eager to get out of their hotels and really plunge into the world. I had said much the same thing myself many times. But I wondered, as I headed back across the Huon Gulf to Lae in a boat packed with people from tiny villages perched on the edge of the sea and the jungle, whether we ever really saw beyond the facade. It was easy to hang out with complicated people from remote places but much harder to know them.

Bennett was feeling optimistic. “The world is a violent and wild place, but that’s the adventure,” he’d told me. “And lightning never strikes twice, right?”

Christy King wasn't so sure when I spoke with her in Lae. The original TV deal the Aussie clients had been trying to negotiate would have required her to accompany them on a hike of the whole track. It collapsed when she refused to take part.

“I would never do it again,” she said, smoking a cigarette behind the high walls of her house, an old habit she’d temporarily resumed after the attack, the only outward sign of its toll. “It’s too dangerous.” King added that, during the incident, she was “worried that the clients might try to do something—they were all big, tough guys, but none tried to be a hero, and they just obeyed and stayed down, so we were lucky. But the Black Cat, unlike Kokoda, is so remote, you can’t do it without carrying large amounts of cash to pay the porters and for everything along the way.”

King loves PNG and always will. But it’s time for her kids to be able to walk to school and play in the streets, she says. For them to have a normal childhood. Though her husband will remain in Lae, tending the family business, she and the kids are moving to Cairns, Australia. Who knows if she’ll ever walk the Black Cat again?