How Cathay Pacific captain spun memories of defying death as a New Guinea bush pilot into an award-winning book

Matt McLaughlin’s early years as a pilot were spent in the vertiginous highlands of Papua New Guinea, some of the most dangerous terrain on earth; years later, he realised others might want to read about his experiences

BEST LAID PLANS I grew up in a town of about 30,000 people, called Gisborne, in New Zealand. I was inspired to be a pilot as a 12-year-old, travelling on a small regional airline. I peered down the aisle into the cockpit and saw the pilots wrestling with the controls. A little light bulb went off.

When I was 18, in 1989, I joined the New Zealand Air Force as a trainee pilot. That was Plan A, but it didn’t work out. It’s a long story, but I got glandular fever and was taken off the course. So I tried Plan B: do the civilian qualifications, and then join Air New Zealand Regional.

That got destroyed when Air New Zealand shut down half of their regional fleet, so I had to go for Plan C. I volunteered to be a missionary – as a pilot.

I thought I’d wind up in South America or somewhere in the Pacific; I had these visions of lying on a beach under a palm tree, and flying four or five days a week between islands. Instead, I wound up in the highlands of Papua New Guinea, at the age of 21, in some of the most dangerous flying conditions in the world. I was there for just under four years.

CRASH COURSE Imagine a slope like Ma On Shan or Tai Mo Shan. Carved into the side of it, at a ridiculous angle, is a runway about 500 metres long. You’re landing on the side of that mountain. It’s filling up your windscreen at a great rate of knots. There’s no margin for error because your airplane’s not powerful enough to climb away and the mountain is hemmed in by other mountains. Once you’ve lined up to land, you’re committed. You might be doing that up to 15 times a day, on 15 different airstrips.

I could hear the passengers screaming over the sound of the engine because they knew they were about to die

It’s fantastic, exciting, but very demanding. Unfortunately, some who weren’t cut out for it were badly injured or died in crashes. My flatmate, who was in his mid-50s with 15 years of experience flying around New Guinea, flew into the side of a mountain and killed himself and 18 passengers two weeks before he was due to retire.

It’s a little better now. The financial and political landscape’s changed and, insurance-wise, not many companies can afford the premiums to fly small planes into the strips. So a lot of strips aren’t serviced any more. It’s a good thing for safety, but it’s a great shame for those isolated communities.

ON A WING AND A PRAYER Several times I landed with my hands shaking. Once, when I was quite new, I descended into a blind valley – I could see the far end through a hole in the cloud. About halfway down, with my wheels just above the treetops, the hole disappeared and I was in the clouds. Now I’m flying blind at the bottom of a valley at 5,000 feet above sea level, with mountains 8,000 feet above sea level on either side. I could hear the passengers screaming over the sound of the engine because they knew they were about to die.

Luckily, my training was good. My boss had said, “If you ever get in trouble in this valley, just steer a little bit to the left of east, and you’ll be safe.” That’s all I focused on. I popped out about 30 seconds later – it felt like an hour. I thought I was going to die, no question. I was waiting to see if I would be killed instantly or if I would hear the sound of the trees coming through the windscreen, or the metallic, wooden, rocky sound of impact.

FLYING HIGH The New Guinea experience was a springboard. I didn’t know it at the time but it’s very well regarded. If a pilot finds out you’ve been in New Guinea, the first thing they say is: “You survived New Guinea; you must be good.”

I don’t know if I’m good, but I’m good enough. And lucky. There were a few situations where I did stupid things, but I was lucky and got away with it. Other people did stupid things and they died. You put up with all sorts as a young person to get to that ultimate goal.

The reason I put up with all the danger – although, to be honest, I loved it – was to gain experience, to join an airline. I got lucky towards the end of 1994, joined Cathay Pacific at age 25 and moved to Hong Kong, where I’ve been based ever since. I wound up about five years ahead of my former air force colleagues. I was a second officer at 25, first officer at 27 and, at 36, I was the captain of a wide-body aircraft. It was 18 years from when I started. I’m in year 22 with Cathay now.

WRITING IT DOWN I had written quite a few notes in New Guinea. When something bad happened, I wrote it down. Maybe because one day I wanted to share it with people. Or maybe it was cathartic: maybe I needed to write it down to stop my hands from shaking. “What did I learn when I almost killed myself today? Don’t do that again.”

The further I got from New Guinea, the more I realised how special the experience was. Once I started the book, most of the chapters came very easily, although it took almost 10 years to get it all out. Just before I finished it, I started approaching publishers. I got the answer I was expecting: “You’ve got a good voice; we like your story. But it’s not commercial enough for us.” Eventually, rather than wait, I decided to do it myself.

The further I got from New Guinea, the more I realised how special the experience was. Once I started the book, most of the chapters came very easily

Normally, self-published books stand out a mile away because they’re done cheaply. My aim from the beginning was for the book not to look like it was self-published. There’s a TV series in the book, too. I’m in the planning stages for that.

HEAD IN THE CLOUDS, FEET ON THE GROUND The safer something gets, the more boring it becomes. I say to my crew: “All this flying is boring,” and I add, “but boring is good. Boring is what we want. And boring is what the passengers want.” So I try to make it as boring as possible.

I’m glad I didn’t know how dangerous the New Guinea flying was, or I would never have been able to keep going. I could go back and do it now; I think I have the skills to do it. But I don’t know if I’d have the balls to do it. I have responsibilities: I have a family, a wife and two boys. If I learned anything from New Guinea it was that it doesn’t matter how good you are, if you stay there long enough, eventually something bad is going to happen to you. I could go back and do 10 more years flying there, and not scratch an aeroplane. But I might crash in the first week. The flying comes with risk, and it’s a risk that I’m no longer willing to accept.

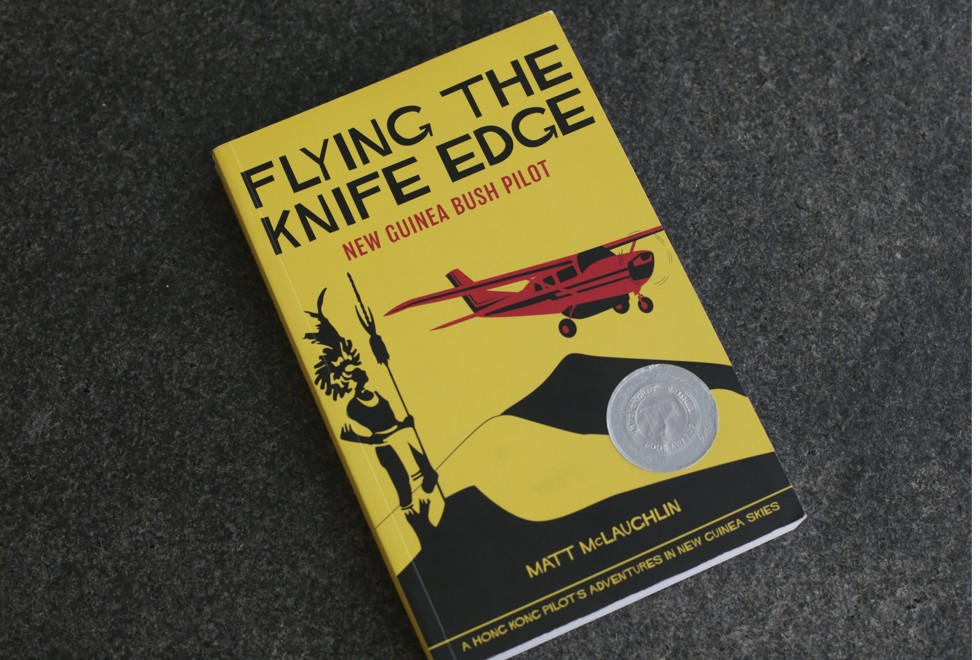

Flying the Knife Edge: New Guinea Bush Pilot (2015) by Matt McLaughlin recently won a silver medal at the 2017 Independent Publisher Book Awards. It is available in bookstores, online and as an e-book.